“Whenever my mother tried to beat the gay out of me, I would think about that sign and fantasize about running away to this almost magical place where it was safe to be gay.” – Paulo Murillo, 2013

In the summer of 2013, a young writer poised a question to the public asking if anyone had information about the long-gone artwork: the West Hollywood Sign (1986-91). This then led him to the EZTV Museum’s Vimeo site and ultimately to the sign’s creator, Michael J. Masucci.

USED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE AUTHOR: We are re-printing below Paulo Murillo’s two moving articles about the West Hollywood Sign:

FIRST ARTICLE ( prior to getting in touch with EZTV):

How many of you remember the vintage and long gone West Hollywood Sign? I recently wrote a love letter of sorts to the City of West Hollywood which is centered around that old sign. The story has been published in the latest issue of The Fight Magazine for Pride, so like check it out.

How many of you remember the vintage and long gone West Hollywood Sign? I recently wrote a love letter of sorts to the City of West Hollywood which is centered around that old sign. The story has been published in the latest issue of The Fight Magazine for Pride, so like check it out.

Oh yeah, thanks to Richard E. Settle for donating his image to this article. There would have been no article without the image, so I’m forever grateful.

Luv,

Me

WEST HOLLYWOODLAND

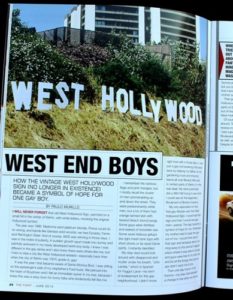

How the vintage West Hollywood sign (no longer in existence) became a symbol of hope for one gay boy.

BY PAULO MURILLO

I will never forget that old West Hollywood Sign, perched on a small hill in the center of WeHo, with white letters, mocking the original Hollywood symbol.

The year was 1986. Madonna went platinum blonde, Prince could do no wrong, and bands like Genesis sold records; we had Dynasty, Fame, and Remington Steel. And of course, AIDS was winning in those days. I was in the midst of puberty. A sudden growth spurt made me clumsy and painfully awkward in my newly developed twink boy body. I knew I was different in the gay sense and I also knew there were others like me, but I had no idea a city like West Hollywood existed–especially back then when the city of WeHo was 100% grade-A, gay!

It was the year I first became aware of Santa Monica Blvd. I was sitting on the passenger’s side of my stepfather’s Ford truck. We pierced into the heart of Boystown and I felt an immediate quiver in my liver, because I knew this was a sissy town for funny folks who kinda/sorta felt like me.

I remember the rainbow flags and pink triangles, but I mostly recall the cluster of men promenading up and down the street. They were predominantly white men, but a lot of them had orange tanned skin with teased bleach-blond bangs. Some guys were shirtless and reeked of forbidden sex. Some wore hideous getups like tight mesh tank tops with short shorts or tie-dyed Genie pants. I instantly identified.

My step-dad would look around with disapproval and mutter under his breath, “Joto Landia,” which is Spanish for Faggot Land – his term of endearment for this gay neighborhood. I didn’t know right from left in those days. I was just a gay kid breaking child labor laws by helping my father do his gardening route and mowing lawns all over Beverly Hills and in certain parts of WeHo (I’m the real deal). My neck practically did a 360/180 trying to see what I could see on the legendary Boulevard of Broken Queens.

My only association to this free gay lifestyle was that West Hollywood Sign. I would see that sign and then I would see gay men – period. The sign became a symbol of hope for me. Whenever my mother tried to beat the gay out of me, I would think about that sign and fantasize about running away to this almost magical place where it was safe to be gay and guys were free to fry their hair and be all the things that grownups didn’t want me to be.

Then one day-horror of all horrors – my step-dad sensed a change in me when we drove past that sign. We were at the stoplight right in front of the Sports Connection gym, which is where the 24-Hour Fitness now stands. A guy crossing the street caught me looking at him, so he blew me a kiss. I felt a shocking Technicolor blush slap me on the face. My father didn’t say anything, but you best believe I got in trouble that night when he told my mom that maricones (look it up) were blowing me kisses. The things my mother said are not suitable for print.

That gay guy blew me a kiss in the wind and I never saw the West Hollywood Sign again, at least not in person. My father avoided the gay parts of Santa Monica Blvd after that little incident. By the time I came out of the closet in 1991 and I braved the bus ride to Boystown, those West Hollywood letters were gone.

Of course, a lot has changed since 1986. My parents eventually came around. Today they not only accept me for who I am, but they also receive my partner into their home. I have been a resident in my beloved “Joto Landia” for well over 15 years, living only a block away from the Boulevard of Broken Queens. A lot has changed in West Hollywood as well, with baby strollers being the norm in the gay parts of the city. Despite the changes, I never forgot that vintage West Hollywood Sign.

A few weeks ago I found an old photo of the sign by the restrooms at Trader Joes in WeHo. The photo inspired me to contact the photographer, Richard E Settle, who would donate that image for this article.

I also wrote a blog asking my readers if they had any information. Several readers lead me to vimeo.com which hosts old EZTV Museum videos where they have actual footage of the unveiling of the West Hollywood Sign in ’86 (visit vimeo.com/48992786).

It turns out the sign was located on the parking lot by the Ramada Plaza next to the Collar and Leash pet store where EZTV used to be – only a block away from where I now live. Artist Micheal J. Masucci of EZTV created this large scale work of “sculptural graffiti,” which was a send-up to pop, film culture, fame, and monumentality. According to EZTV Museum, the work stood from 1986-1991, which means I came out of the closet as the sign came down. People kept stealing the letters, which EZTV would replace. I’m told at one point the sign read Wet Ho. The letters continued to be stolen. New letters were not made one day and the sign slowly disappeared.

“Do you remember the old West Hollywood Sign?” I asked my friend Judd. “I do,” he responded. “It was a shitty little sign on a dirty little hill.”

It may well have been a shitty little sign, but those old letters saved me in a way and helped me accept myself as gay. That sign also led me to the city where I live today–Hello West Hollywood! Many moons later I still love you. Now bring back the West Hollywood Sign! Kiss, kiss.

Read more commentary by Paulo Murillo at: thehissfit.com

SECOND ARTICLE (after getting in touch with EZTV):

Throwback to the Vintage West Hollywood Sign

If you lived, played or passed through West Hollywood in the mid-80s to early 90s, it’s likely you came across the long gone and mostly forgotten West Hollywood Sign — a tongue-in-cheek, large-scale sculptural graffiti art installation that was a sendup to the original Hollywood symbol.

The West Hollywood sign is unveiled outside EZTV on April 15, 1986. (Photo courtesy of Sallie M. Fiske Papers and Photographs / ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.)

Located on a hill at the parking lot outside of what was then home to EZTV video center (where Collar and Leash now stands, next to the Ramada Plaza on Santa Monica Boulevard), the West Hollywood Sign was a city landmark that quickly became a tourist attraction.

Today, the small hillside next to the Ramada Inn remains, but the West Hollywood sign is long gone. (Photo by Paulo Murillo)

Decades before there was a rainbow crosswalk on Santa Monica and San Vicente, the West Hollywood sign was a symbol of freedom and acceptance in the heart of WeHo — not just for LGBT people, but also for Russian Jewish immigrants and crazy rock -‘n’- rollers who turned to WeHo for a safe place to party. The sign also was used as a backdrop for candidates running for city office. The rotating mayor would pose for pictures and hold press conferences in front of the sign, which sealed it as part of the city.

Artist Micheal Masucci created the sign for EZTV as a salute to West Hollywood. EZTV was part of a new era in video entertainment and WeHo was the melting pot where change was happening. The sign was a monument to the newly established city and a send up to video art, pop music, film culture, fame.

Today, EZTV remains an avant-garde video production company and digital art center. It was founded in 1979 by video pioneer John Dorr and a team of independent writers, actors and technicians. Way before YouTube became what it is today, EZTV was creating video art and producing critically acclaimed video projects with little to no budget.

According to their website (eztvmedia.com), EZTV studio in WeHo was a large space that housed the first 100 seat video theatre, as well as one of the earliest digital art galleries in history.

“The very front part of the space was a public space,” Masucci said. “There was a large screening room and art gallery. That space was used for lots of different things. ACT UP and Queer Nation would have meetings there and plan their activities. The front area was really part of the community.”

The City of West Hollywood was only two -years old, making it the newest city in the country when the West Hollywood Sign was erected on April 15, 1986. Masucci spent $50 on cheap plywood to create the sign. EZTV had an unveiling ceremony that also celebrated the 30th anniversary of the invention of video tape. The unveiling was filmed as a performance art event, attracting an onslaught of onlookers as well as several news reporters.

“At the time we took it as a joke,” Masucci said. “We thought, ‘Hollywood is the world capital of film, so West Hollywood is the world capital of video.’ When we put the sign up, we did it without permission. We never asked the landowner, so we expected it to be up for five days and we would be court ordered to tear it down. But we quickly saw that it meant a lot more than we first imagined. What started out sort of as a joke, ended up staying up for five years instead of five days. It really became a symbol for a lot of people, for a community and for a cause. It celebrated diversity and liberation.”

Video had long killed the radio star in 1986. Madonna was newly married to Sean Penn and sold millions of “True Blue” records. Janet Jackson released “Control,” Prince was still with The Revolution and people who looked like Phil Collins and Billy Joel were music superstars. Parachute pants were the fashion rage, as were mesh shirts, acid washed jeans, fingerless gloves, shoulder pads, and oversized shirts in bright neon colors.

Fashion dysfunctions aside, it was also a dark time for a gay community that was losing thousands of young gay men to HIV/AIDS.

WeHo was hit hard by the pandemic.

“Most of the people passed fast.” Masucci said. “Families were not that open to their sons being gay, so when a lot of people were diagnosed, their families abandoned them. There were many times when a young man passed and there was no place to do a short memorial service. EZTV had a small service for somebody, almost every weekend – most people we never knew.”

Masucci also recalls empowering times in WeHo in the early 80s.

“That tiny little piece of land called West Hollywood wasn’t officially a city until the mid-80s. It was in legal limbo, so nobody was exactly sure who had to enforce the law, so it was easier to party for everybody.” Masucci said. “It attracted many communities that I certainly had nothing to do with, but all kinds of people went to West Hollywood because it was a place they could be free. And that was something we were really, really aware of and we took great pride in it being our home. It meant a lot of things to us.

“I think the sign conveyed that here we were – these tiny nobodies with no money who could stand proud and say we were where the real news was happening. This was the place where change was going to take place. Some people took it seriously. Understandably, most people didn’t and we didn’t take offense to that.”

People loved the West Hollywood sign so much, some walked away with a letter or two as souvenirs, leaving Masucci with the task of restoring the sign. Images of the sign also started appearing in shady places.

“What a lot of people would do, which would piss us off, is that they would take some cheap shots of the Hollywood sign, cropping out the ‘West,’ so we’d end up seeing it in a girlie magazine and shit like that.” Masucci said. “We’d see some blond bimbo standing topless in front of the sign and it would just say ‘Hollywood.’”

Letters continued to go missing. Masucci stopped replacing them one day and the West Hollywood Sign slowly vanished in mid-1991.

It was the beginning of the end of an era. Dorr died of complications from AIDS in 1993 (Masucci assumed the role as director after his death) and a year later EZTV was unable to afford the space on Santa Monica Boulevard. It was forced to move to a smaller space on Hollywood Boulevard, before moving to its current location in the city of Santa Monica.

A year ago EZTV began the process of archiving its extensive collecting of video art. Masucci tells WEHOville that it plans to shut down EZTV after 30 years in the business within the next year. He hopes to preserve EZTV’s history.

Part of that history is reminding people about the West Hollywood Sign.

“We never thought the sign was going to be embraced by so many different people, but for the most part, it has disappeared from memory. It’s not even in people’s collection of West Hollywood history, “Masucci said. “It’s still interesting to see that it did have an impact beyond what even we were about.”