John Dorr’s vision of the wide-spread use and acceptance of feature-length narrative cinema created on home analog video equipment, of course, never came to pass. At least not in the way he envisioned. Even today, almost never is a low-cost narrative feature film widely seen or distributed. The 2013 Academy Award nominated film “The Beasts of the Southern Wild” (which cost $1.8 million) is a rare exception.

Later in 2013, major Hollywood director Steven Spielberg was to announce his grim vision of Hollywood’s future, saying that it would “implode” resulting in only the rare blockbuster as likely to receive widespread theatrical distribution.

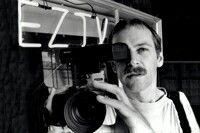

In many ways, it was YouTube that found the magic formula for no-cost independent work with its viral videos often shot on a smart phone, grabbing a worldwide attention. John Dorr may have taken great exception to the following statement, but in so many ways, EZTV anticipated the advent of YouTube rather than the future of Hollywood. I don’t say this as an insult, but actually, my intention is complimentary.

With today’s digital 4K standard, productions are often as expensive as when shot on film and digital effects actually make productions more expensive. High-end productions, with bigger and bigger budgets, have become more the norm. This may ultimately change, but has not yet. The recent movie theater distribution experiments with 3D, 48FPS, and IMAX, demonstrate that audiences will pay a premium to still see work they cannot experience at home. Or in a park on their digital tablet.

It was actually documentaries that best, initially, benefited from low-cost video technology. Cinema verite and location-based field production adapted well to the evolving video “porta-packs”, then camcorders, and other relatively low-cost tools. When the Empowerment Project (previously another guest exhibitor at EZTV) won the Academy Award for best feature documentary in 1993, the year John Dorr died, independent video production had taken its place alongside film as a viable medium for serious professional level documentary production. It would still take quite some time before any non-film based digital cameras became viable for narrative feature production. It would be George Lucas, in developing his “Star Wars” prequels, and then James Cameron, with “Avatar”, that would redefine what a video camera (now called a digital camera) could be. Neither of these legendary producer/directors are known for productions which are inexpensive.

John Dorr’s interviews by the late 1980′s had a more and more defeated and, perhaps, almost bitter tone. His dream of video theaters around the country, screening works by independent filmmakers, never came to pass, except for the advent of the ‘micro-cinema movement’. For the most part, analog video was simply never adequate, either in picture or sound quality, to even compete with low-end film production. Betamax never was, nor would ever be, a viable way to make movies.

It would be, of course, a decade later when the computer and digital camcorder were finally at a quality level where the world would take notice. EZTV contributed to this through its early advocacy and implementation. Along with artists ia Kamandalu, Victor Acevedo, Michael Wright, Joan Collins, Coco Conn, Robert Gelman, and curator Patric Prince, among others, an early articulation of the impending power of personal computing took shape at EZTV well before the general acceptance among mainstream art circles. EZTV became Los Angeles’ true center for the early desktop digital revolution. Any other assertion is simply nonsense.

Today, the investigation of EZTV’s diverse and multi-purposed role in media art history is in the hands of those who can bring some objectivity to the history. Hopefully they will ask the right questions and look in the right places for the clues as to just how important EZTV was in shaping the independent video scene in California.

Today, the investigation of EZTV’s diverse and multi-purposed role in media art history is in the hands of those who can bring some objectivity to the history. Hopefully they will ask the right questions and look in the right places for the clues as to just how important EZTV was in shaping the independent video scene in California.

The modern contemporary art space, which routinely combines static art with projected media often with a live performative component, was rare in Los Angeles when EZTV was formed. By the end of the 1980′s, the EZTV model of combining live performance, electronic media, and curatorial collaboration migrated to many other spaces, often without recognition. Now this type of exhibition is ubiquitous around the world.

Among the many communities which EZTV championed and served, the central role of its many LGBTQ founding members is clear. Although decimated by the AIDS pandemic in the 1980′s and early 1990′s, EZTV persevered and continued amid seemingly impossible odds. As Michael Kearns (Hollywood’s first openly gay actor) stated, EZTV became an “AIDS survivor”. That survival was at a considerable cost, both emotionally as well as financially, to the core EZTV artists who chose to keep EZTV alive. EZTV’s story after founder Dorr died in 1993 became just as important as the years in which Dorr ran the space.

Among the many communities which EZTV championed and served, the central role of its many LGBTQ founding members is clear. Although decimated by the AIDS pandemic in the 1980′s and early 1990′s, EZTV persevered and continued amid seemingly impossible odds. As Michael Kearns (Hollywood’s first openly gay actor) stated, EZTV became an “AIDS survivor”. That survival was at a considerable cost, both emotionally as well as financially, to the core EZTV artists who chose to keep EZTV alive. EZTV’s story after founder Dorr died in 1993 became just as important as the years in which Dorr ran the space.

In my view, John Dorr and early EZTV’s greatest legacy is the understanding that time-based media, such as video deserves and exhibitional approach which acknowledges that its similarities to cinema are greater than the art world’s typical presentational paradigm of displaying video as if it was a painting. The exception, of course, would be video installation where the video content has no specific beginning, middle, or end.